|

| Fans line up to return Hernandez jerseys (Boston.com) |

According to a recent ESPN.com story, "EA Sports, the maker of the popular video games 'Madden NFL 25' and 'NCAA Football 14,' has opted to remove former New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez from each game." This story might initially make one think that the whole "innocent until proven guilty" judicial system that the United States operates with has been replaced by vigilante justice (though admittedly the vigilantism here is rather tame in historical terms). However, while the world of our courts and the world of Playstations are ever drawing closer and closer to each other, there is still no law that requires video games companies—or NFL teams—to wait until justice has been done by the courts to begin to administer their own brand of justice.

What is of more importance here then is the question of "Why?" What was it about Hernandez's alleged crime that has led the Patriots (admittedly, my NFL team) to remove him from the team and his jerseys along with him, and now EA Sports to remove him from the digital world? An answer can perhaps be found in Walter Benjamin's famous essay "Critique of Violence" from 1921. In this essay Benjamin distinguishes "mythic violence" from "divine violence," or the violence that is "lawmaking" from the violence that is "law-destroying":

If mythical violence is law-making, divine violence is law-destroying; if the former sets boundaries, the latter boundlessly destroys them; if mythical violence brings at once guilt and retribution, divine power only expiates; if the former threatens, the latter strikes; if the former is bloody, the latter is lethal without spilling blood. The legend of Niobe may be confronted, as an example of this violence, with God's judgment on the company of Korah. It strikes privileged Levites, strikes them without warning, without threat, and does not stop short of annihilation. (Reflections, 297).

Mythical violence, according to Benjamin, can be thought of in terms of the gods Artemis and Apollo destroying Niobe's family for her arrogance, or, in more recent terms, can also be thought of as what Keyser Söze did to those Hungarians who dared to attack his family in his absence. In both cases we are meant to learn from this violence, to remember what happens to those who cross the gods or who cross Söze, and thus this memory serves as the inauguration of a law. This form of law-creation operates then on a parallel with Nietzsche's story from the Genealogy of how medieval torture was used to instill "five or six 'I will not's'" into those humans who had not yet learned how to play nice with others, or in other words, to be a citizen.

Divine violence, on the other hand, is a violence that wipes away any trace of both the crime and the punishment. Söze left one Hungarian alive to tell of what happened, but God, like EA Sports, leaves no such remainders or reminders. As Benjamin explains, this violence is concerned with "expiation," an expiation aimed not at removing guilt from the sinner, but at removing law from the living. Whereas law uses mythical violence as "bloody power over mere life for its own sake," God uses divine violence as "pure power over all life for the sake of the living." Hence, "the first demands sacrifice, the second accepts it." In other words, Artemis, Apollo, and Söze use violence in order to affirm their standing in the world, while God and EA Sports use violence in order to maintain the world.

So what world are the Patriots and now EA Sports trying to maintain? A world where football and murder do not coincide. By removing any trace of Aaron Hernandez, the NFL has been expiated of sin, or so the Patriots and EA Sports hope. Their aim then is not to teach other football players or fans of football a lesson about the value of the real-world over and above the value of games, but rather to preserve games as free of the sins of the real-world. Games therefore reign supreme, not the players, not the fans, and not our judicial system.

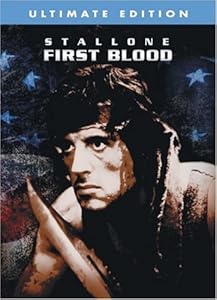

This is important, not necessarily because of what it means for Aaron Hernandez, but for what it reveals about the parallel situation regarding veterans and society (N.B. by "parallel" I'm not suggesting that veterans are murderers or alleged murderers, but rather that they are perhaps treated in a parallel fashion nonetheless). As absurd as it may sound today, the first Rambo movie, First Blood (1982), is perhaps the best pop-culture example of what I am here referring to. John Rambo, having just returned from Vietnam, having just failed to reconnect with who he

|

| Go watch it, I'll wait... |

believed to be the sole remaining member of his elite special forces unit, finds himself now lost. Sheriff Teasle, as the local authority, or representative of divine power, comes across Rambo and offers to give him a lift. In the ensuing conversation Teasle sizes up Rambo as someone who would find their small town of Hope to be too "boring" for "someone like him" and proceeds to thus do Rambo the favor of driving him through town, past all the restaurants Rambo was hoping to eat at, and across a bridge where he drops him off and advises him that there's a place to eat a few miles down the road.

This crossing of the bridge serves as a poignant metaphor for the treatment of not only returning Vietnam veterans, but of the now returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. Teasle does not arrest Rambo or try to kill Rambo (at least not initially) but simply drives him out of town, out of Hope, out of the "boring" world of peace, and back to the wilderness of what in my book I am calling exile. The veteran is allowed to exist, but only so long as he exists somewhere else, somewhere far enough away to expiate the rest of us from the sins of war, sins therefore that we created but that they took upon themselves to live with. When the veteran does not abide by these rules, he is then either attacked in an attempt to remind him that he is not above the rules (as happens to Rambo, as well as to Nicolas Cage's returning veteran in Con Air (1997)), or he is diagnosed as someone who is no longer capable of living in accordance with the rules (as happens whenever we diagnose someone with "war nerves," "solder's heart," "shell shock," "PTSD," or "TBI").

Aaron Hernandez and Rambo thus serve to remind us, with the help of Walter Benjamin, that, like children, we do not clean up our messes, but rather pretend they simply do not exist. As Nietzsche said, to forgive is not to forget, but rather to forget that one forgot. We are currently in the process of forgetting Hernandez and veterans, and soon we will forget that we forgot, though of course with the aim of not forgiving them, but of forgiving ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment